Cardboard box, 220 x 157 x 25 cm, UV print, 4 pieces

The Extant Collection narrates the true story of Güner Coşkunsu, an archaeologist in Mardin who fought against the destruction of archaeological sites throughout her career. Some authorities intentionally and consciously tarnished Coşkunsu’s presumption of innocence to remove her from her profession altogether. Coşkunsu exposed the authorities' disregard for significant archaeological findings, including Paleolithic artifacts deemed insignificant and slated for burial. Following Coşkunsu's death, an artist, moved by the injustice, secretly excavates the buried artifacts for a year, finding boxes adorned with images of endemic plants instead.

Cardboard box, 220 x 157 x 25 cm, UV print, 4 pieces

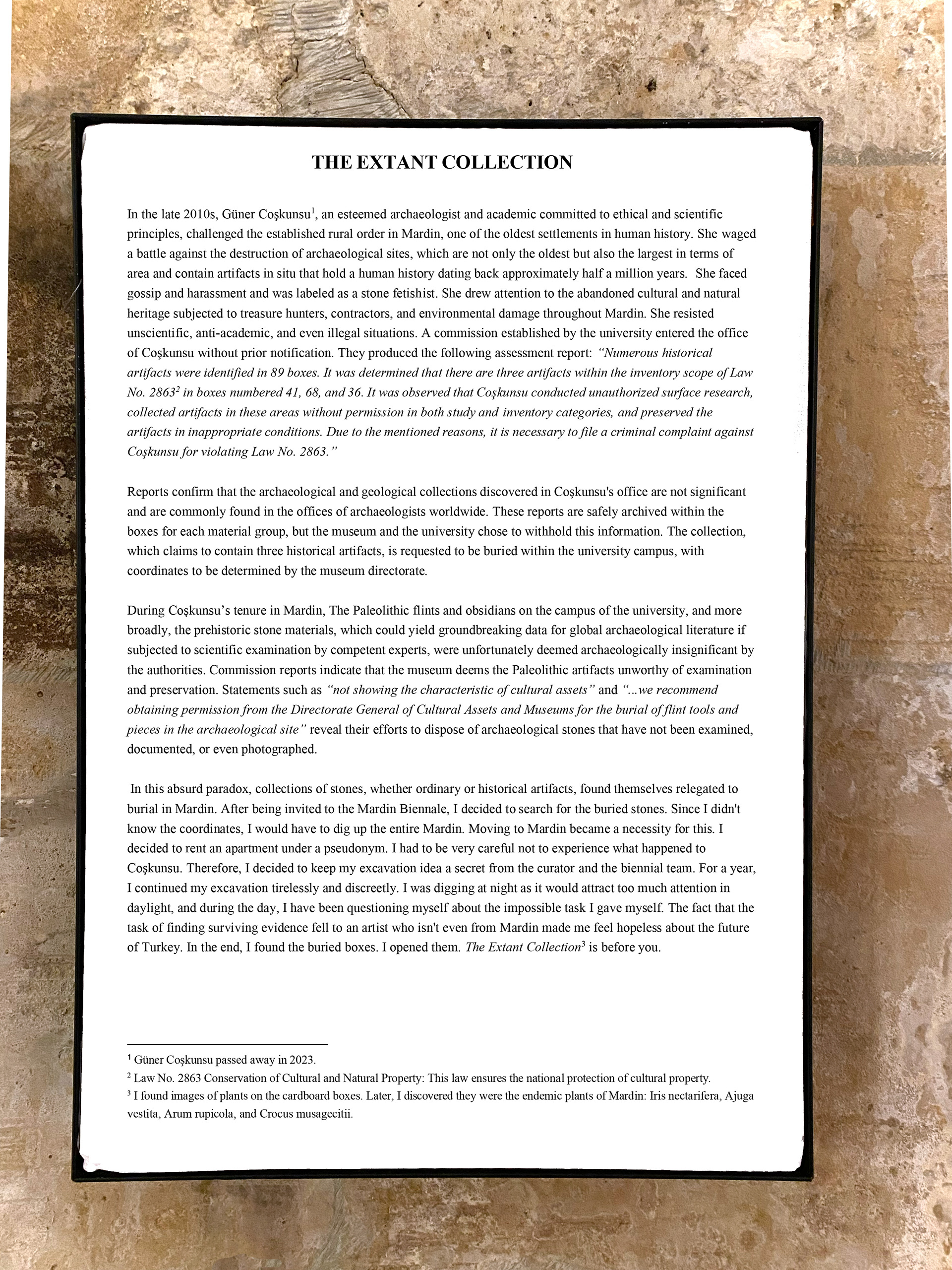

Cardboard box, 220 x 157 x 25 cm, UV print, 4 pieces, Lightbox, A3 size, "The Extant Collection" text both in TR and ENG

THE EXTANT COLLECTION

In the late 2010s, Güner Coşkunsu¹, an esteemed archaeologist and academic committed to ethical and scientific principles, challenged the established rural order in Mardin, southeastern Türkiye, one of the oldest settlements in human history. She waged a battle against the destruction of archaeological sites, which are not only the oldest but also the largest in terms of area and contain artifacts in situ that hold a human history dating back approximately half a million years. She faced gossip and harassment and was labeled a stone fetishist. She drew attention to the abandoned cultural and natural heritage subjected to treasure hunters, contractors, and environmental damage throughout Mardin. She resisted unscientific, anti-academic, and even illegal situations.

A commission established by the university entered Coşkunsu’s office without prior notification. They produced the following assessment report: “Numerous historical artifacts were identified in 89 boxes. It was determined that there are three artifacts within the inventory scope of Law No. 2863² in boxes numbered 41, 68, and 36. It was observed that Coşkunsu conducted unauthorized surface research, collected artifacts in these areas without permission in both study and inventory categories, and preserved the artifacts in inappropriate conditions. Due to the mentioned reasons, it is necessary to file a criminal complaint against Coşkunsu for violating Law No. 2863.”

Reports confirm that the archaeological and geological collections discovered in Coşkunsu's office are not significant and are commonly found in the offices of archaeologists worldwide. These reports are safely archived within the boxes for each material group, but the museum and the university chose to withhold this information. The collection, which claims to contain three historical artifacts, is requested to be buried within the university campus, with coordinates to be determined by the museum directorate.

During Coşkunsu’s tenure in Mardin, the Paleolithic flints and obsidians on the campus of the university—and more broadly, the prehistoric stone materials that could yield groundbreaking data for global archaeological literature if subjected to scientific examination by competent experts—were unfortunately deemed archaeologically insignificant by the authorities. Commission reports indicate that the museum deems the Paleolithic artifacts unworthy of examination and preservation. Statements such as “not showing the characteristic of cultural assets” and “...we recommend obtaining permission from the Directorate General of Cultural Assets and Museums for the burial of flint tools and pieces in the archaeological site” reveal their efforts to dispose of archaeological stones that have not been examined, documented, or even photographed.

In this absurd paradox, collections of stones—whether ordinary or historically meaningful—found themselves relegated to burial in Mardin. After receiving an invitation to the Mardin Biennial, I decided to search for the buried stones. Since I did not know the coordinates, I would have had to dig up the entire Mardin. Moving to the city became a necessity. I rented an apartment under a pseudonym and kept my excavation secret from the curator and the biennial team, determined not to experience the same fate as Coşkunsu. For a year, I continued my excavation tirelessly and discreetly. I dug at night to avoid attention, and during the day, I questioned myself about the impossibility of the task I had given myself. The fact that the responsibility of finding surviving evidence had fallen to an artist who was not even from Mardin made me feel hopeless about the future of Türkiye. In the end, I found the buried boxes. I opened them. The Extant Collection³ is before you.

1 Güner Coşkunsu passed away in 2023.

2 Law No. 2863 Conservation of Cultural and Natural Property: This law ensures the national protection of cultural property.

3 I found images of plants on the cardboard boxes. Later, I discovered they were the endemic plants of Mardin: Iris nectarifera, Ajuga vestita, Arum rupicola, and Crocus musagecitii.

Cardboard box, 220 x 157 x 25 cm

Cardboard box, 220 x 157 x 25 cm

Cardboard box, 220 x 157 x 25 cm

Cardboard box, 220 x 157 x 25 cm

MEVCUT KOLEKSİYON

2010'ların sonlarına doğru, etik ve bilimsel prensiplere bağlı saygın bir arkeolog ve akademisyen olan Dr. Güner Coşkunsu¹, dünyanın insanlık tarihine dair en eski yerleşim yerlerinden biri olan Mardin’deki yozlaşmış düzene karşı meydan okudu. Türkiye’de ve hatta Yakın Doğu’daki en eski, alan olarak en büyük ve in situ buluntuları içeren, yaklaşık yarım milyon yıl öncesine dayanan insanlık tarihine ev sahipliği yapan çok ender Paleolitik yerleşim yerlerinin yok olmasına karşı bir mücadele başlattı. Dedikodu ve tacize maruz kaldı. Taşperest olarak etiketlendi. Mardin genelinde define avcıları, müteahhitler ve çevresel tahribata maruz kalan kendi kaderine terk edilmiş kültürel ve doğal mirasa dikkat çekti. Bilimsel olmayan, anti-akademik ve hatta yasa dışı durumlara karşı direndi. Üniversite tarafından oluşturulan bir komisyon, Dr. Güner Coşkunsu'nun üniversitedeki odasına girerek şu tespit raporunu oluşturdu: “89 kutu içinde çok sayıda tarihi eser tespiti yapıldı. 41, 68 ve 36 No’lu kutular içinde 2863 sayılı yasa² kapsamında envanterlik mahiyette 3 adet eser olduğu tespit edilmiştir. Coşkunsu’nun izinsiz yüzey araştırması yaptığı, bu alanlarda izinsiz etütlük ve envanterlik mahiyette eserler topladığı, eserleri uygun olmayan ortamlarda muhafaza ettiği görülmüştür. Belirtilen nedenlerden dolayı Coşkunsu hakkında 2863 sayılı yasaya muhalefetten adli makamlara suç duyurusunda bulunulması gerekmektedir.’’

Yurt içi ve uluslararası laboratuvarlar ve arkeolog akademisyenler, Dr. Güner Coşkunsu'nun ofisinde bulunan arkeolojik ve 2863 kapsamında olmayan jeolojik koleksiyonun eser sınıfında olmadığını ve hatta bu tür malzemelerin Türkiye'deki ve dünyadaki herhangi bir arkeoloğun ofisinde bulunabileceğini doğrulayan raporlar sunmuşlardır. Bu raporlar, her malzeme grubu için ait oldukları kutularda güvenli bir şekilde arşivlenmiştir, ancak müze ve üniversite bu bilgiyi saklamayı tercih etmiştir. Bahsi geçen taşların, koordinatları müze müdürlüğü tarafından belirlenerek üniversite alanı içine gömülmesi talep edilmiştir.

Coşkunsu'nun Mardin'deki görev süresi boyunca, üniversite kampüsündeki Paleolitik döneme ait çakmaktaşları ve obsidyenleri, hatta genel olarak prehistorik taş malzeme, yetkin uzmanlar tarafından bilimsel bir incelemeye tabi tutulması durumunda dünya arkeoloji literatürü için çığır açıcı verilere ulaşabileceği halde, ne yazık ki yetkililer tarafından arkeolojik olarak önemsiz olarak değerlendirildi. Komisyon raporları, müzenin Paleolitik taşları incelemeye ve saklamaya değer bulmadığını belirtmektedir. “Kültür varlık özelliği göstermeyen”, “… çakmaktaşı alet ve parçalarının tekrardan sit alanına gömülmesi için Kültür Varlıkları ve Müzeler Genel Müdürlüğü’nden izin alınmasını önermekteyiz” gibi ifadelerle, henüz incelenmemiş, belgelenmemiş, çizimleri yapılmamış ve hatta fotoğrafı bile çekilmemiş arkeolojik taşları gömme kararı aldılar.

Bu paradoksal düzende taşlar, sıradan ya da tarihi eser fark etmeksizin, kendilerini gömülürken buldular. Mardin Bienali’ne davet aldıktan sonra gömülen taşları bulmaya karar verdim. Koordinatları bilmediğim için tüm Mardin’i kazmam gerekecekti. Bunun için Mardin’e taşınmam şart olmuştu. Sahte bir isimle ev tutmaya karar verdim. Güner Hanım’ın başına gelenleri yaşamamak için çok dikkatli olmalıydım. Bu nedenle kazı fikrimi bienal ekibinden ve küratörden saklamaya karar verdim. Bir yıl boyunca bıkmadan ve usulca kazı çalışmalarımı sürdürdüm. Gündüzleri çok dikkat çekeceği için geceleri kazıyordum. Gündüzleri ise bu imkânsız görevi neden üstlendiğim ile ilgili kendimi sorguluyordum. Kanıtları bulma görevinin Mardinli bile olmayan bir sanatçıya düşmesi, Türkiye’nin geleceği ile ilgili umutsuzluğa kapılmama neden oldu. Sonunda gömdükleri kutuları buldum ve içlerini açtım. Mevcut Koleksiyon³ huzurunuzda.

¹ Dr. Güner Coşkunsu 2023 yılında vefat etti.

² 2863 Sayılı Kültür ve Tabiat Varlıklarını Koruma Kanunu: Bu Kanunun amacı; korunması gerekli taşınır ve taşınmaz kültür ve tabiat varlıklarına ilişkin tanımları belirlemek, yapılacak işlem ve faaliyetleri düzenlemek, bu konuda gerekli ilke ve uygulama kararlarını alacak teşkilatın kuruluş ve görevlerini tespit etmektir.

³ Kutuların içerisinde, daha sonra Mardin iline ait olduğunu öğrendiğim endemik bitki imgeleri buldum: Iris nectarifera, Crocus musagecitii, Arum rupicola ve Ajuga vestita.

² 2863 Sayılı Kültür ve Tabiat Varlıklarını Koruma Kanunu: Bu Kanunun amacı; korunması gerekli taşınır ve taşınmaz kültür ve tabiat varlıklarına ilişkin tanımları belirlemek, yapılacak işlem ve faaliyetleri düzenlemek, bu konuda gerekli ilke ve uygulama kararlarını alacak teşkilatın kuruluş ve görevlerini tespit etmektir.

³ Kutuların içerisinde, daha sonra Mardin iline ait olduğunu öğrendiğim endemik bitki imgeleri buldum: Iris nectarifera, Crocus musagecitii, Arum rupicola ve Ajuga vestita.