“Scripted Expanded Molded I” exhibition view, 2022, Istanbul

Throughout the exhibition, I return to the notion of parergon—the supplemental, the excessive, the thing at the edge of the work that simultaneously frames it and destabilizes it. I think of both works in this way: as frames, supports, things that hold a space or a question. They are not objects as much as propositions. If there is a fourth Medusa and a fourth table, what comes after the third? What happens when the leftover becomes the measure? When the mold is mistaken for the thing itself?

This exhibition is a study in inversion, misrecognition, and the limits of legibility. It is also, quite simply, a script expanded, a mold remade.

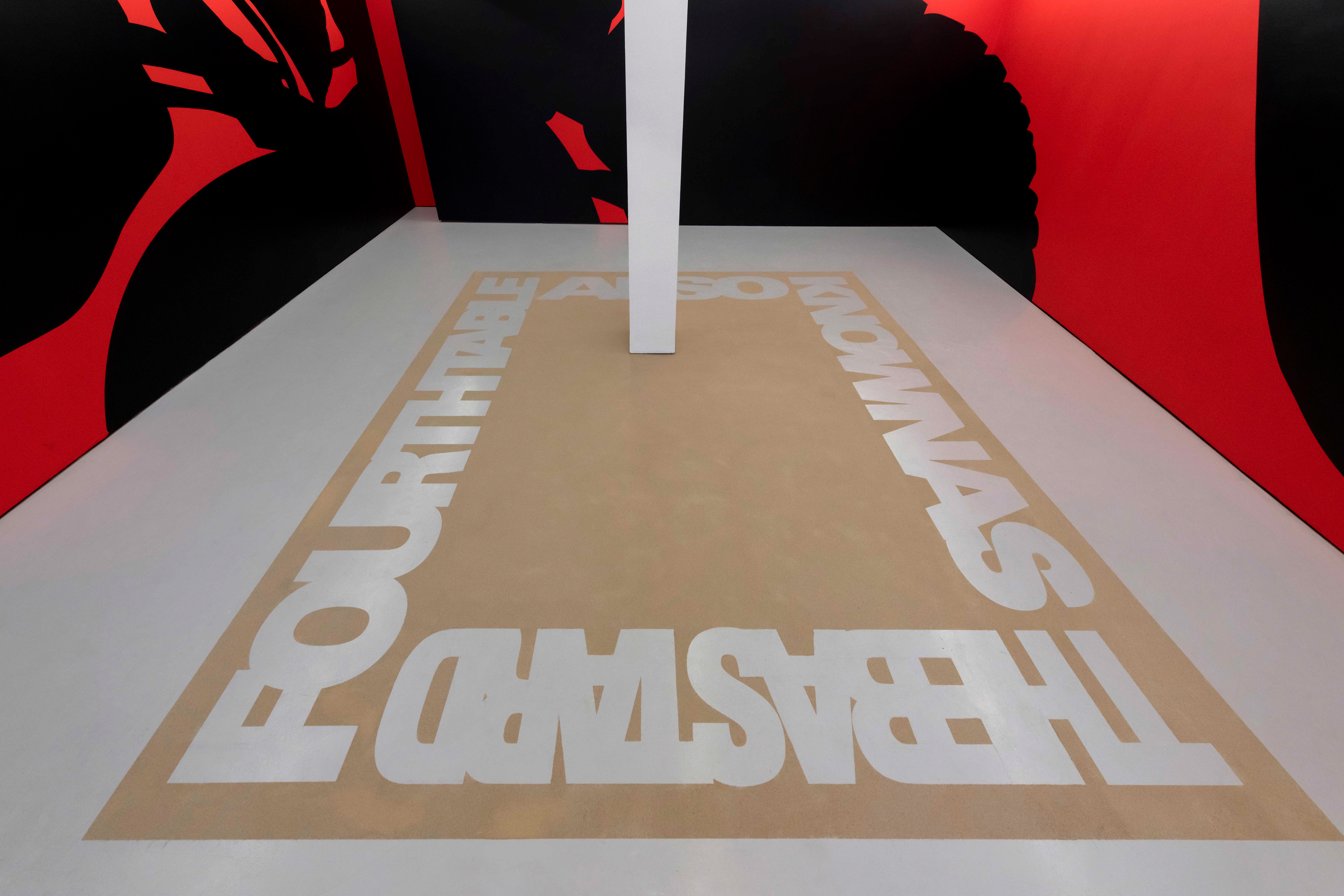

The exhibition unfolds through three main works—Fourth Medusa, Fourth Table also known as the Bastard, and Fourth Apple—together with four live performances. Each extends my ongoing interest in molds, spolia, and frames—forms that exist as supports, borders, or temporary structures yet end up shaping meaning. The Fourth Medusa monumentalizes the mold itself, assembled in fiberglass from the fragmented surface of Istanbul’s ancient Medusa heads. Fourth Table turns the gallery floor into a sand-drawn outline, refusing the form of the table and stepping aside as a “bastard” parergon. Fourth Apple fragments and expands a familiar still-life motif across the gallery walls, linking histories of perception and representation back to questions of framing. The performances were based on my text Fourth Table also known as the Bastard, translated into graphic scores in a collab with a composer and activated live in the gallery. Together, sculpture, text, and sound weave questions of myth, mediation, and the conditions of making into a fourth movement that insists on remaining slightly outside.

Scanned from the original Medusa head in the Basilica Cistern and carved from polyurethane foam, fiberglass, and stainless steel bolts.

250 x 156 x 172, 2022

The Fourth Medusa is a mold—fiberglass, fragmented, bolted together, derived from photogrammetry scans of the existing Medusa heads in Istanbul. It isn’t marble, and it isn’t whole. It isn’t even a sculpture in the traditional sense. It’s a container for something that will never be cast. In modeling the mold itself, I was thinking about the tension between form and its reproduction, between myth and material, and the way some fragments are used to support everything else—sometimes literally, as in the cisterns, and sometimes structurally, conceptually. I was also thinking about spoliation, and bastard forms—how things get used out of context, inverted, laid on their sides, turned into function.

“Scripted Expanded Molded I” exhibition view, 2022, Istanbul

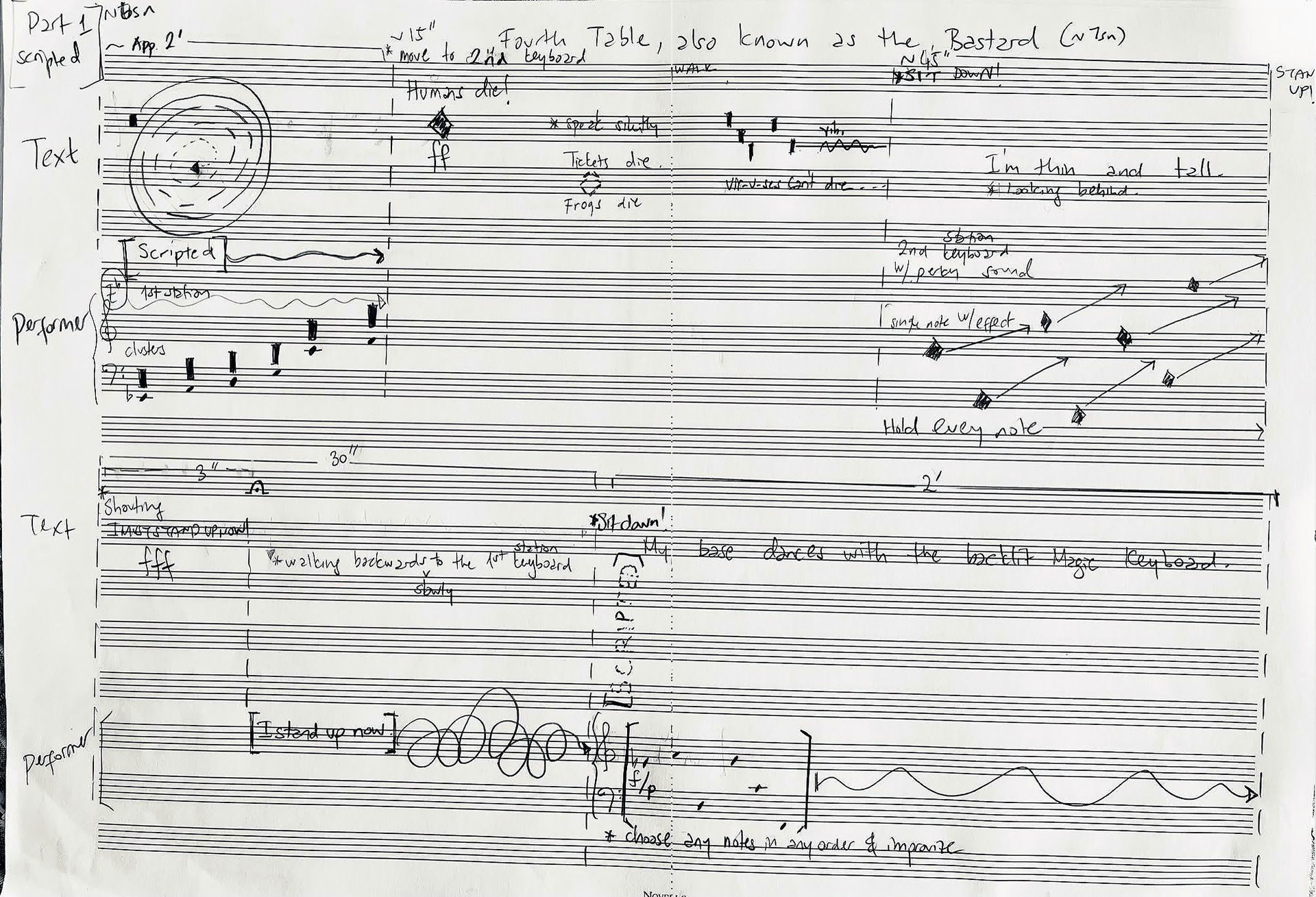

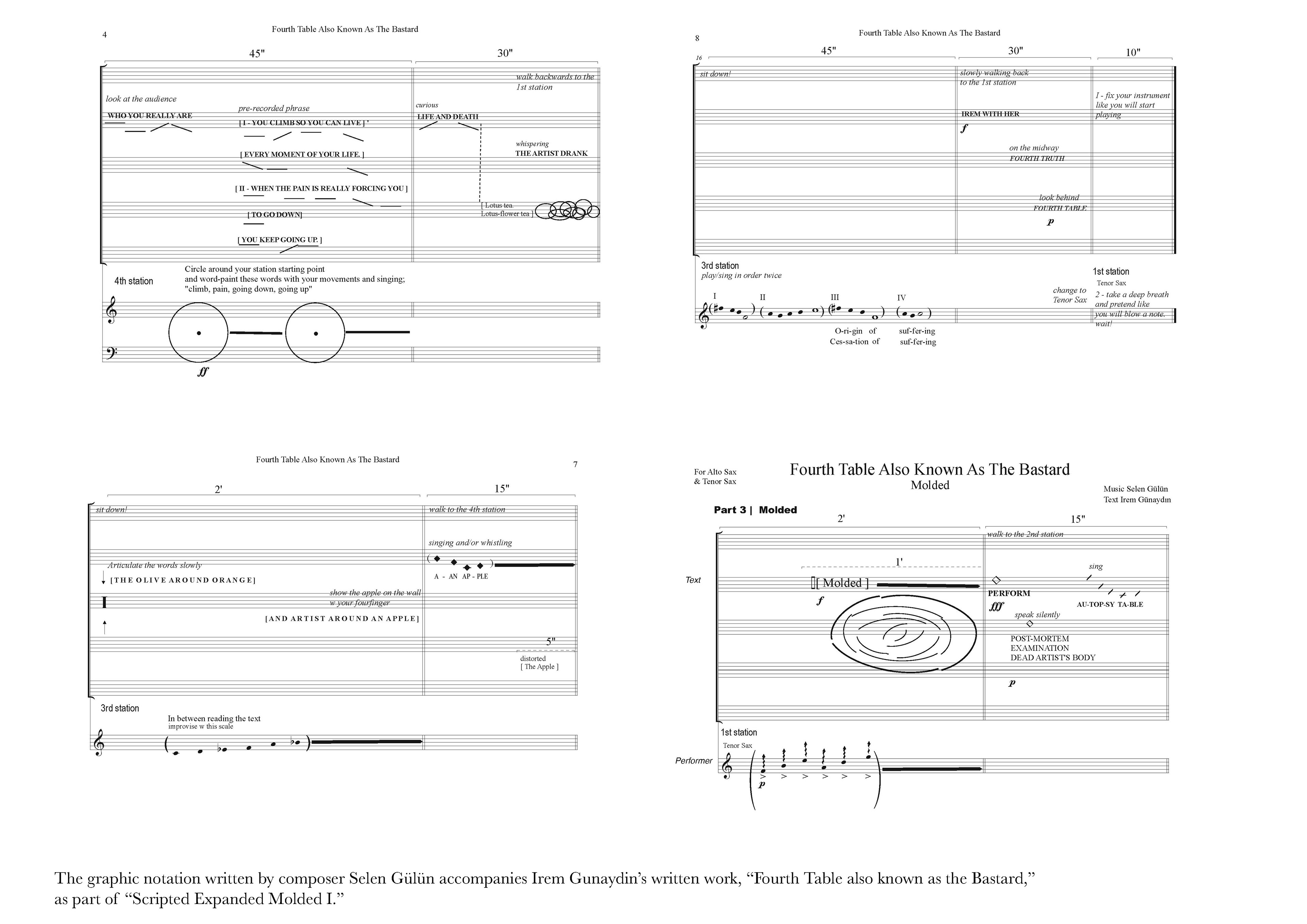

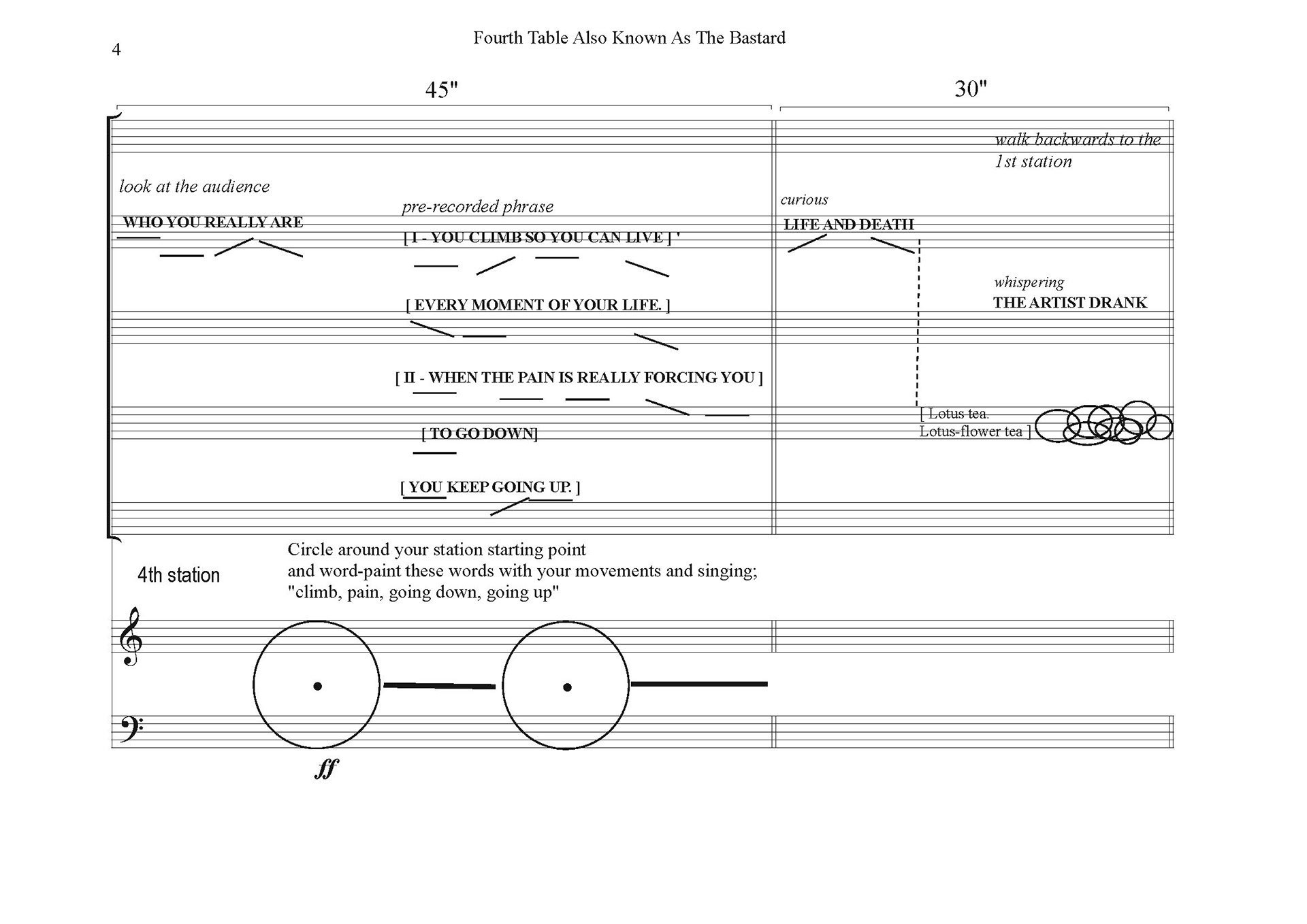

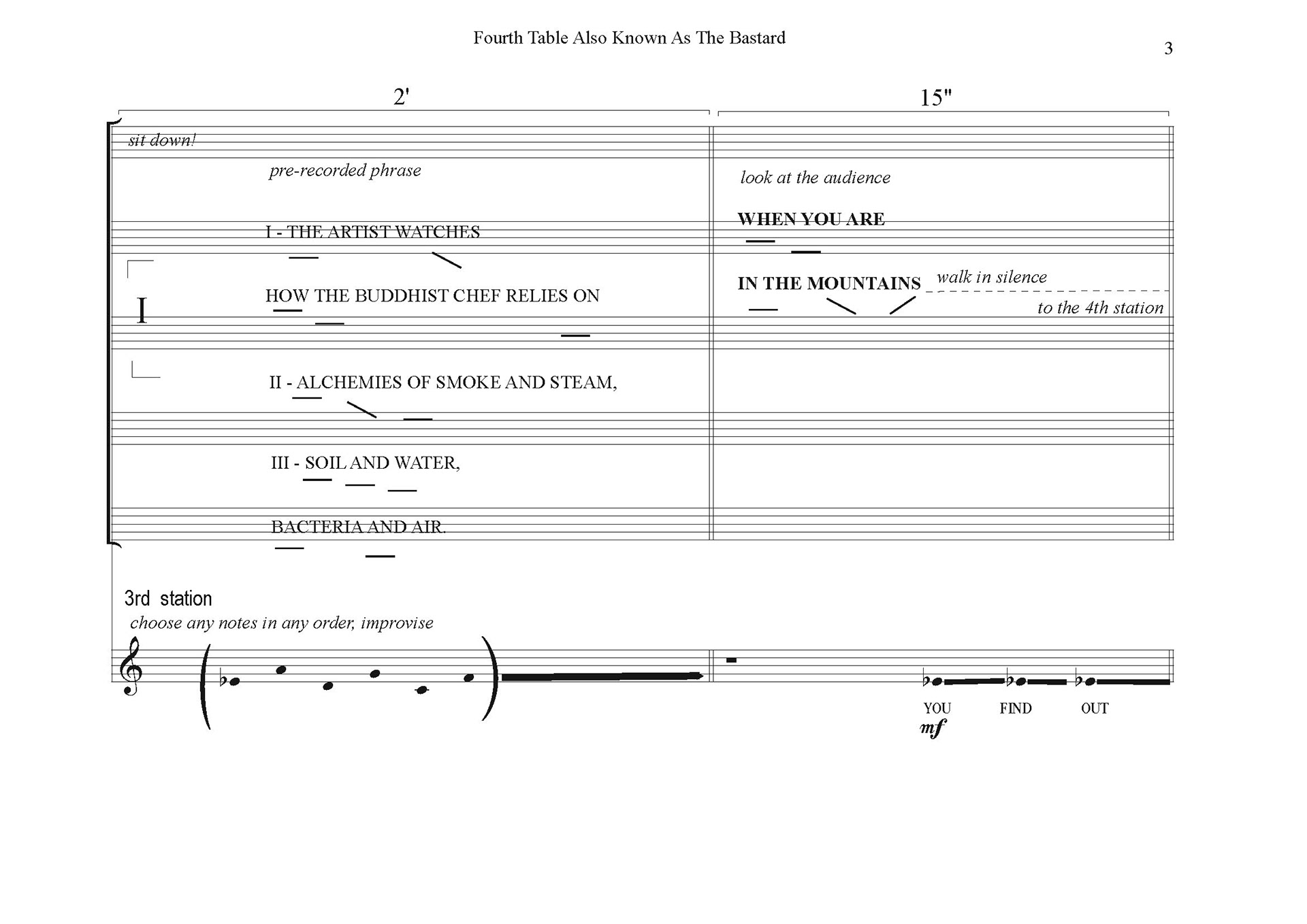

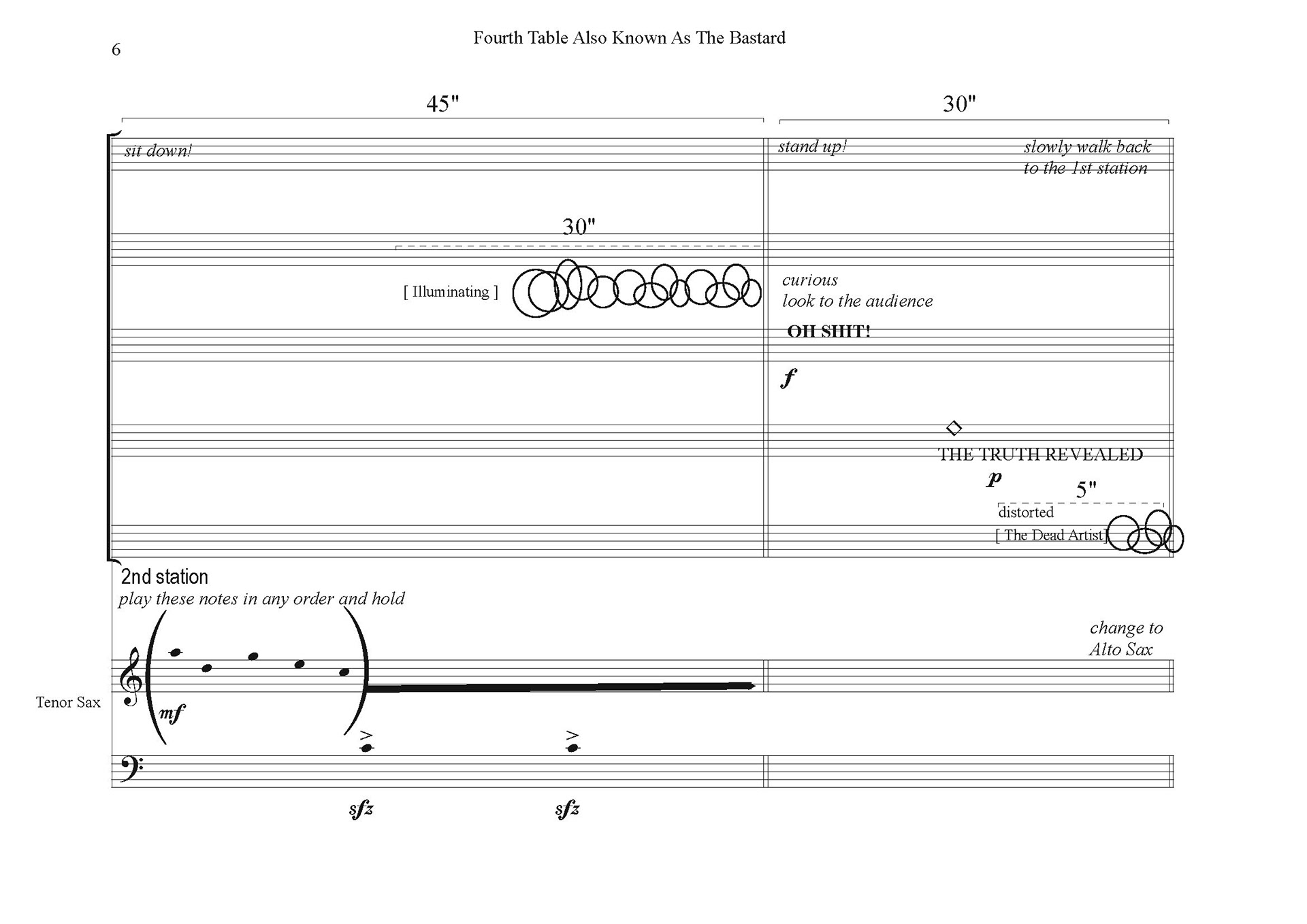

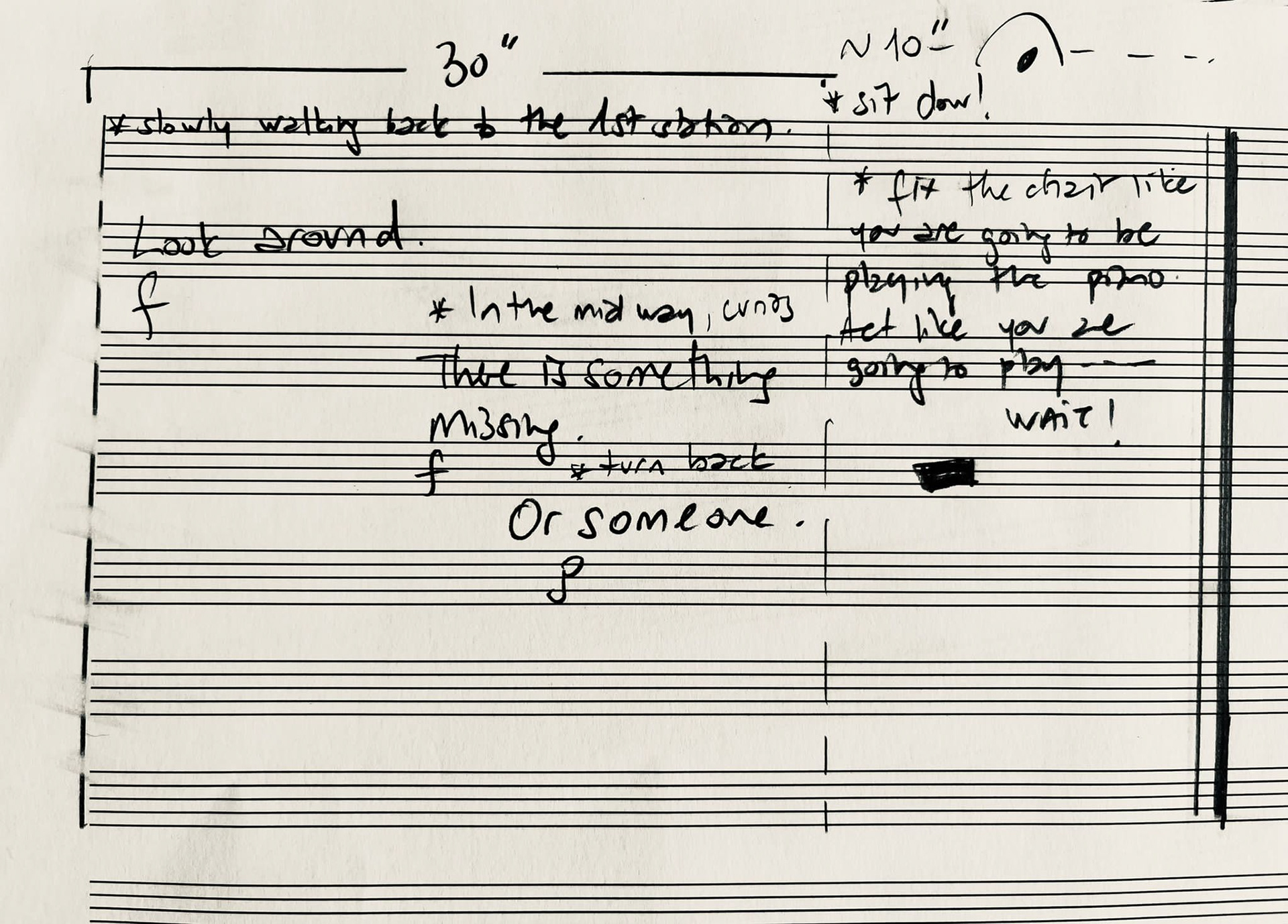

The graphic notation written by composer Selen Gülün accompanies Irem Gunaydin’s written work, “Fourth Table also known as the Bastard,” as part of “Scripted Expanded Molded I Scripted Expanded Molded I.”

The bastard comes up again in the Fourth Table. It began as a response to Arthur Eddington’s two tables—the one you see and the one science describes—and Graham Harman’s philosophical third. Mine is the fourth: a sand frame in the shape of the gallery itself, a negative form, a non-table, a place that gestures toward sitting, gathering, measuring—but refuses any stable identity. Around it, an apple’s silhouette runs across the walls, echoing the history of still life, but also the cycles of revolution, perception, and digestion. The apple and the table: two recurring signs in how we understand both matter and meaning.

“Fourth Table Also Known As the Bastard,” 2022 quartz sand, 650 x 533 cm

“Fourth Medusa,” 2022 Scanned from the original Medusa head in the Basilica Cistern and carved from polyurethane foam, fiberglass, stainless steel bolt. 250 x 156 x 172

Details from the “Fourth Table Also Known As the Bastard,” 2022 quartz sand, 650 x 533 cm

The graphic notation written by composer Selen Gülün accompanies Irem Gunaydin’s written work, “Fourth Table also known as the Bastard,” as part of “Scripted Expanded Molded I.”

“Fourth Medusa,” 2022 Scanned from the original Medusa head in the Basilica Cistern and carved from polyurethane foam, fiberglass, stainless steel bolt. 250 x 156 x 172

The graphic notation written by composer Selen Gülün accompanies Irem Gunaydin’s written work, “Fourth Table also known as the Bastard,” as part of “Scripted Expanded Molded I.”

Details from the “Fourth Table Also Known As the Bastard,” 2022 quartz sand, 650 x 533 cm

“Fourth apple” (apple silhouette on the wall) , vinyl, dimension variable, 2022

“Fourth apple” (apple silhouette on the wall) , vinyl, dimension variable, 2022

Carving the head of Medusa

Carving the column

Graphical scores composed by jazz musician Selen Gülün, inspired by İrem Günaydın’s text “Fourth Table also known as the Bastard.” Created on the occasion of the exhibition “Scripted Expanded Molded I,” these scores were performed live as part of the exhibition, translating the written work into musical notation and temporal experience.

Graphical scores composed by jazz musician Selen Gülün, inspired by İrem Günaydın’s text “Fourth Table also known as the Bastard.” Created on the occasion of the exhibition “Scripted Expanded Molded I,” these scores were performed live as part of the exhibition, translating the written work into musical notation and temporal experience.

Graphical scores composed by jazz musician Selen Gülün, inspired by İrem Günaydın’s text “Fourth Table also known as the Bastard.” Created on the occasion of the exhibition “Scripted Expanded Molded I,” these scores were performed live as part of the exhibition, translating the written work into musical notation and temporal experience.