Published as part of İrem Günaydın’s exhibiton “Salad Cake” Edition of 250

In Salad Cake, I started with something small and absurd: a dish I once saw at a café called “salad cake”—not quite a salad, not quite a cake, but something in between. That slippage between categories became the ground for this exhibition. I was thinking about what exists on the edge of things, what’s decorative, discarded, supplemental, and how that might be central to the way we understand art, labor, and identity.

At the center of the exhibition is a video work where I mix my voice with others, Morpheus from The Matrix, a French-accented narrator, to tell a speculative story involving Poussin, Cézanne, and Magritte, all caught between the dream of painting and the problem of truth. The video is accompanied by prints, sculptural gestures, and a letter I wrote to myself, an artist writing to her non-artist self, who also works as a currency exchange officer. That letter, titled 'Flaschenpost: I Owe You the Truth in Painting and I Will Tell It To You,' moves through the works like a message in a bottle: unsure of its destination, but sent anyway.

The works in Salad Cake don’t offer a clean resolution. Instead, they ask what happens when the frame becomes part of the image, when cooking becomes a kind of composition, when parody becomes a way to speak honestly. This show is about thresholds, between art and non-art, between figure and ground, between who I am and who I am not.

"A Portrait of the Artist as a Vinyl Bunny," 2020, vinyl, 100x300cm

Exhibition view from the “Salad Cake,” 2020, The Pill | Istanbul

Exhibition view from the “Salad Cake” 2020, The Pill | Istanbul

“Fabric vestibule,” 2020, emboss print on fabric, 400 x 74 cm

Exhibition view from the “Salad Cake,” 2020, The Pill | Istanbul

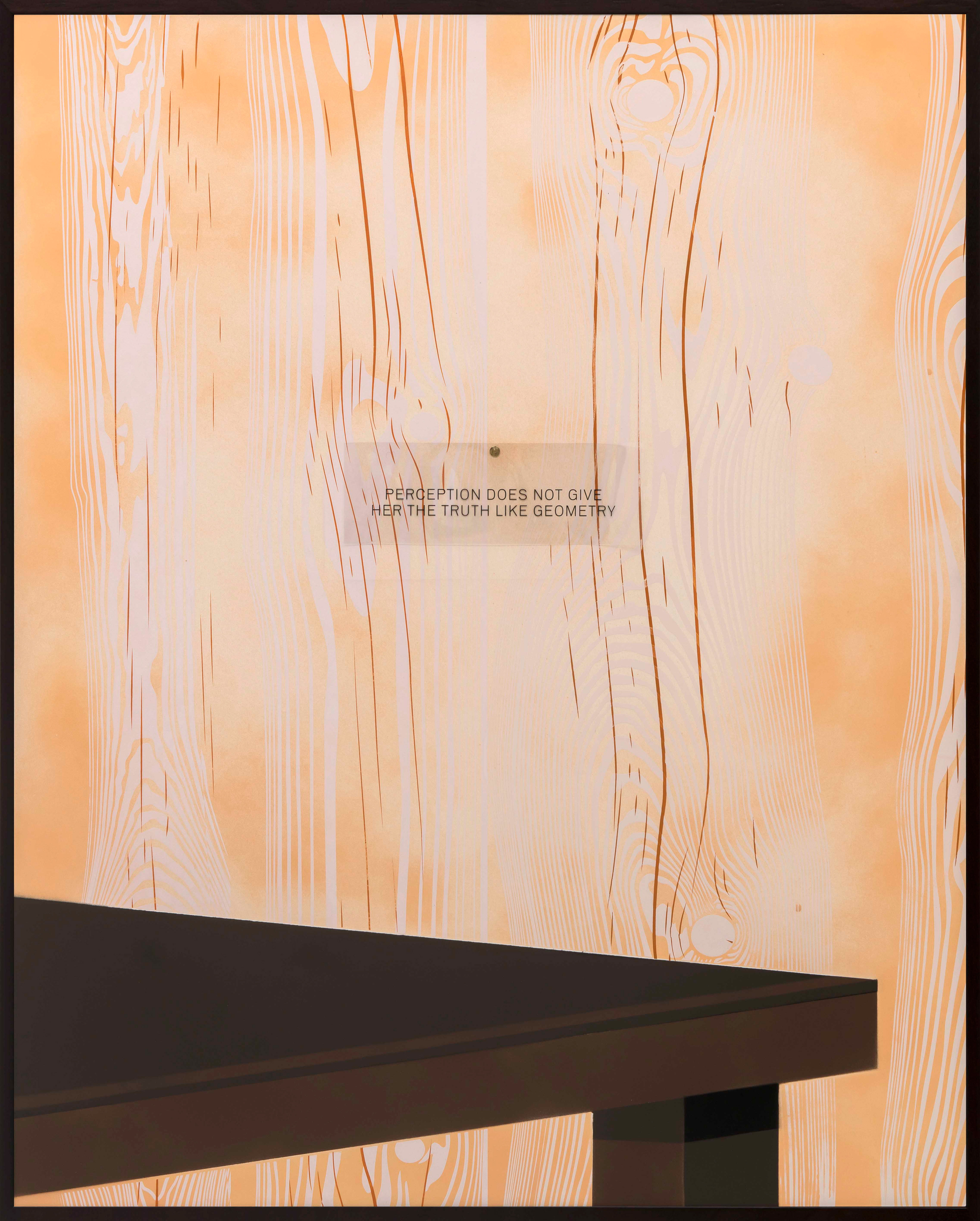

“The Integrals,” 2020, Stencil on pasteboard, two colors silkscreen print, acetate, 100 x 80 cm

Exhibition view from the “Salad Cake,” 2020, The Pill | Istanbul

Exhibition view from the “Salad Cake,” 2020, The Pill | Istanbul

“The Integrals,” 2020, Stencil on pasteboard, two colors silkscreen print, acetate, 100 x 80 cm

Exhibition view from the “Salad Cake,” 2020, The Pill | Istanbul

Exhibition view from the "Integrals,” 2020, The Pill | Istanbul

Exhibition view from the "Decimal Fraction,” 2020, The Pill | Istanbul

“Decimal Fraction,” 2020, Photogrammetry

“Decimal Fraction,” 2020, Photogrammetry, MJF print (Multi Jet Fusion), 80 x 63 cm

“The Integrals,” 2020, Stencil on pasteboard, two colors silkscreen print, acetate, 100 x 80 cm

“FLASCHENPOST: I OWE YOU THE TRUTH IN PAINTING AND I WILL TELL IT TO YOU” 2020, 21’’46’

“FLASCHENPOST: I OWE YOU THE TRUTH IN PAINTING AND I WILL TELL IT TO YOU” 2020, 21’’46’

“FLASCHENPOST: I OWE YOU THE TRUTH IN PAINTING AND I WILL TELL IT TO YOU” 2020, 21’’46’

Exhibition view from the “Salad Cake,” 2020, The Pill | Istanbul

Exhibition view from the “Salad Cake,” 2020, The Pill | Istanbul

A LOVE OF HORS D’OEUVRES

Almost exactly one year before this exhibition, there was a late-night conversation between Irem and me. We were sitting on one of the long tables arranged in the studio of Leyla Gediz: it was a New Year’s feast party. People surrounded us, there was food in front of us, our glasses were full, and we talked in length about the concept of “Parergon.” The word comes from Greek, merging “para-” and “ergon”; it designates all that is besides, in addition to, or outside “the work of art.” While it may simply refer to the frame or the ornamental elements, in Derrida’s thought, it expands to include the artwork’s negative space and its borders, as that which simultaneously stabilizes and sets in motion the work of art. In French, the exact translation would be “Hors d’oeuvre,” universally known as the culinary term for small portions of food served outside the main course - often to encourage a guest to drink more.

A year later, we are at The Pill, in an exhibition titled “Salad Cake,” standing before a video installation. The camera moves back and forth between fruits and vegetables scattered across a table, all-in close-up views. A voiceover, the artist’s voice mixed with the voice of Morpheus from The Matrix and a male voice speaking English with a French accent, recount a story about four art historical characters confronting the truth of painting and a choice between the “dreamworld” and the “desert of the real,” which turns out not to be a choice, but rather a provocation to fold them together. A letter from herself as an artist about herself as a non-artist: and then there are vertical views of cooking gestures: separating egg yolks on one and macerating berries on the other. I keep thinking that in an invisible way, what frames them all together is the studio of Leyla Gediz (A painter’s studio) once again, where Irem produced this exhibition, where we saw each other last summer. A painter’s table constitutes the ground upon which these fruits and vegetables are scattered. Both outside and inside Irem’s works. What we have here is a whimsical play across mediums, weaving art into non-art and back into art again.

Irem Gunaydin is interested in the conditions of the possibility of art making. This is another way of stating that she is interested in the frame and the ground rather than the image-as-representation, in what happens between context and canon, between work and frame on the one hand, and between process and oeuvre on the other. She is also interested in perforating the tightly knit textures of art history and the matter of her own identity as an artist. The former, she does by diving deep into art historical canon with a focus on categories of still life and landscape, of naturalism and baroque – dissolving these categories themselves in an exploration of the plasticity of their subject matter and material conditions. The latter, she does with a form of address most subjective yet grounded in the everyday: the epistolary form. A text titled “Flaschenpost: I Owe You the Truth in Painting and I Will Tell It To You,” written by the artist, acts as a pass-partout throughout the exhibition. The latter part of the sentence is borrowed from correspondence between two painters, Paul Cézanne and Emile Bernard, Cézanne being the one uttering the sentence and confessing a debt of truth in painting. A debt taken up by Jacques Derrida to reflect on the same subject matter in an eponymously titled book, a debt which, now, Irem seems to take up in her own letter, adding one word to the sentence: Flaschenpost. It means “message in a bottle” in German. So, it isn’t just the epistolary form connecting Irem Gunaydin in a conversation with Cézanne and Derrida and connecting us as readers to all of them in a confessional mode of address, but also the idea of a distance in time and space, which is operative here. The medium is the message, and in this case, its truth lies in declaring the uncertainty of its reception: when, where, and by whom? How long is the distance, and what is the fold in time? This idea of an unstable yet undeniable distance, along with those of distinction and composition, are central to the exhibition: between artist and audience, between self and shadow, figure and background, subject matter and frame, mask and face, between the surface of the painting and the grid of the canvas. This becomes clearer through Irem’s folding of art history outside in, using the margins to destabilize the center, scratching the elitism of high art with eruptions of the everyday and the popular. Three canonical figures, Poussin, Cézanne, and Magritte, appear as characters in her narrative, confronting the question of which pill to choose in Matrix: red or blue? Irem’s response is not to choose but to “fold” in different ways to arrive at constellations of red and blue. Similarly, the Judgment of Paris, one of the most depicted Greek mythological scenes since the Renaissance, is no longer a matter of choosing between Hera, Aphrodite, and Athena but a problem of juxtaposing beats during a DJ’s gig, of varying the emphasis to achieve varying effects. And then, there is the repetitive doubling of Irem herself: Irem, the artist, and Irem, the currency exchange officer, dancing with each other in a shifting geometry of figure and background. They constitute each other’s subconscious, never knowing each other completely. They appear contradictory, but they are complementary, pushed together, and pulled apart by gravitational forces. We are at once confronted with the economic reality of life as an artist and the problem of recognition of art making as labor: back to conditions of possibility of art making.

In her imaginary dialogues, Irem has a tongue-in-cheek way of interweaving threads of art historical canon with anecdotal knowledge from and around major art historical figures and themes, entangling them with visual references from 20th-century popular culture – Bugs Bunny as the animated figure piercing the fabric of the film, or Sylvester the Cat’s ease at shifting between dimensions. Thus arriving at a punctured texture that allows space for movement, breath, and potentialities in multiple directions. In Derridean terms, we would speak of subjectile, an eruption of the ground through the figure, a protrusion of art by its outside. Circling back to the message in the bottle, what Irem’s letter and videos lay bare is the open space between the letter’s externalization and its arrival at its destination, where the speculative and the teleological processes of signification coexist without the necessity of correspondence.

Text by Asli Seven